A Detailed History

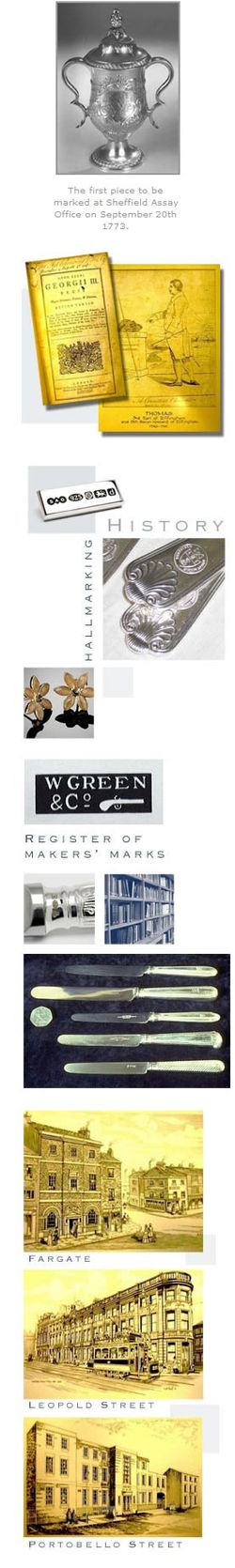

There has been an Assay Office in Sheffield since 1773 when local silversmiths, who resented the inconvenience of having to send their wares to London for hallmarking, joined with Birmingham petitioners to ask Parliament for their own Offices. Despite fierce opposition from the London Goldsmiths' Company, an Act of Parliament (shown here) was passed, granting Sheffield the right to assay silver.

Because the Select Committee which considered the petition had uncovered so many abuses by the existing Assay Offices of the time, Parliament made sure that the new ones were more strictly controlled. The Act appointed thirty local men, including Thomas, the 3rd Earl of Effingham (shown below) as 'Guardians of the Standard of Wrought Plate within the Town of Sheffield' to supervise the work of the Office.By restricting the number of Guardians who were silversmiths to fewer than ten, Parliament also made sure that the Office was run for the benefit of the consumer rather than the manufacturer.

The day to day running of the Office was entrusted to an Assay Master who had to take his oath before the Master of the Royal Mint and enter into a Bond for £500. The Office was to be non-profit making and its running costs were to be met by the hallmarking charges paid by the manufacturers.

More than two hundred years later, the Office is still funded in exactly the same way.

Originally, Sheffield had the right to mark all silver goods produced within a twenty mile radius of Sheffield. After the second Sheffield Act of 1784, the Office also had the right to keep a Register of all makers' marks (shown below) on plated silver wares made within one hundred miles radius - which of course included Birmingham.

From 1836 this Register unfortunately fell into disuse, but before then Sheffield and Birmingham frequently quarrelled over Sheffield's monopoly, and Sheffield occasionally threatened to prosecute Birmingham makers for using unregistered marks. Possibly this explains why more Birmingham platers than Sheffield registered their marks.

The 1773 Act had empowered Sheffield to use a Crown for its town mark. The story goes that this was because the Birmingham and Sheffield petitioners for the Act met at the 'Crown and Anchor', an inn situated off The Strand in London, and that each town adopted one of these signs as its mark. Certainly the inn existed - but whether there is any truth in the story is unknown. After 1903, when Sheffield was finally allowed to assay and mark gold as well as silver (the result of a clause in the Sheffield Corporation Act), Sheffield had two town marks - the Crown for silver and the Rose for gold.

For the first eleven years the Sheffield Assay Office struggled to survive, borrowing heavily from local silversmiths. By using mass-production methods for stamping out thin silver, Sheffield made very light wares which competed strongly with heavier London-made goods. Assaying, however, was charged for by weight. Over 100 knife handles (shown below) could be marked for only five pennies - a price which did not reflect the time and effort involved. The only way to make ends meet was to increase charges. The Act of 1784 charged for small articles by count instead of weight. As a result, the Office's fortunes revived.

The first Assay Office was a rented house on Norfolk Street and the first Assay Master a Londoner, Daniel Bradbury. The Office only opened on Mondays and Thursdays, although Mr. Bradbury was allowed to open on a third day for private assays.

In 1774 the Office moved to a court off Norfolk Street "lately occupied by Thomas Boulsover" - the inventor of Old Sheffield Plate. By 1795 the Office had moved again, this time to a brand new building on Fargate (shown below).

In the nineteenth century, Sheffield became a major manufacturing centre with an international reputation for its silver and cutlery. Production continued to grow rapidly and it became obvious that the Office could no longer cope unless its opening hours increased. When, in 1880, the Fargate premises were needed for road-widening, the Guardians acquired a new site in Leopold Street (shown below) and remained there until 1958. By this time, however, the demand for silver goods had fallen dramatically and the building was much too large.

Before the World War II, 1,250,000 ozs of silver passed through the Office each year.

By 1958 this had fallen to 300,000 ozs. Many large local firms closed and it seemed as though the only people still making silverwares were skilled craft-workers. The Office moved again, this time to a much smaller building in Portobello Street (shown below).

After the Hallmarking Act was passed in 1973, the nature of the work submitted to the Assay Office changed. No longer were the main customers the traditional Sheffield silversmiths producing large pieces of hollow-ware. Goods from all over the United Kingdom and abroad came in to be assayed, and foreign gold (especially 9ct gold chains) became very important. The extra workload involved by this increase in smaller articles necessitated re-development - initially within the existing building, to streamline the laboratories and make more marking space.

In the early 1970s the hallmark became an important feature in jewellery design, Jack Spencer used the largest size of hallmark as decoration on a range of gold and silver jewellery. A pair of cufflinks are held within the Sheffield Assay Office collection.

A cheaper alternative then appeared, in which the mark was placed vertically down a rectangular block to make 'dog-tag' pendants, and these, especially when they incorporated the Special Mark to celebrate the Queen's Silver Jubilee, became phenomenally successful.

The income from this extra work was used in alterations to make the Goldsmiths' Wing to create more marking space, and the foundation stone was laid by Ian Threlfall, Prime Warden of the Goldsmiths' Company, in October 1978. More space for marking was created by renting office space elsewhere in the town and converting the existing offices into marking rooms. Meanwhile, the Office bought the former 'Willow Tree' public house next door and fitted it out for offices and marking. By now the British Hallmarking Council was pressing for an expansion of hallmarking facilities in Britain, so the Office also bought the Charleston Works on Orange Street adjacent to the 'Willow Tree' room for more building.

In March 1983 Sir Frederick Dainton, then Prime Warden of the Goldsmiths' Company, laid the foundation stone of the Guardians' Hall. The new building was completed in 1985 and officially opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (shown below) in December 1986. It provided extra space for offices, laboratories, staff facilities, Board Room and Library.

The Hallmarking Act of 1973 removed many restrictions on marking and consolidated many earlier Acts. It was based on the Trade Descriptions Act and made it an offence to sell almost anything as gold, silver or platinum unless first assayed and marked. For the first time, all the Offices adopted the same date-letter and alphabet. After 200 years, Sheffield lost its Crown mark for silver and used the Rose on both gold and silver. Platinum was not assayed in Sheffield until June 1975, mainly because of the cost of the equipment needed, but testing and marking were finally introduced to meet local customers' demands.

Throughout its long and fascinating history, the Office has continued to adapt to customers' needs and to introduce innovative new processes.

In 1997 laser marking was introduced for hollow and delicate articles such as necklaces, watch-cases and bangles, which would have been damaged by traditional 'punching' methods.

Other services, such as nickel-free testing for jewellery and mercury-screening for occupational exposure, complement traditional assaying and hallmarking.

January 1999 saw the introduction of additional (lower) standards for gold, silver and platinum to enable free competition within the European Community. For the first time the date-letter became voluntary rather than compulsory, and the sterling lion mark and crown gold mark also became optional. Now all goods are marked with their standard of fineness in parts per thousand, and it is no longer possible to distinguish between British and foreign-made articles.

In 2007, the introduction of new legislation for 'mixed metals' marking meant that items such as jewellery and watches that are made from a combination of metals such as silver and titanium or gold and stainless steel could now be hallmarked.

Sheffield Assay Office had lobbied hard to bring about the legislation, seeing it as of particular relevance to contemporary designers working with mixed metals and providing greater scope and encouragement for them to explore more creative designs. The changes also benefit retailers and consumers alike, as a mixed metal hallmark is an endorsement and authentication of content.

Whilst assay and hallmarking continues to be an important part of the Sheffield Assay Office business, an ongoing investment in research and development has seen the the organisation move into advanced analytical services - with clients that range from high street retailers of fashion jewellery to international healthcare companies.

The significant growth of this business has prompted yet further investment - in a purpose-built single storey assay, analytical and research facility to which the Sheffield Assay Office moved in July 2008.

More than 250 years after it first opened its doors, Sheffield Assay Office still protects consumers and manufacturers alike, maintaining its reputation for integrity and efficiency.

We are proud of our history but we will always move with the times too.